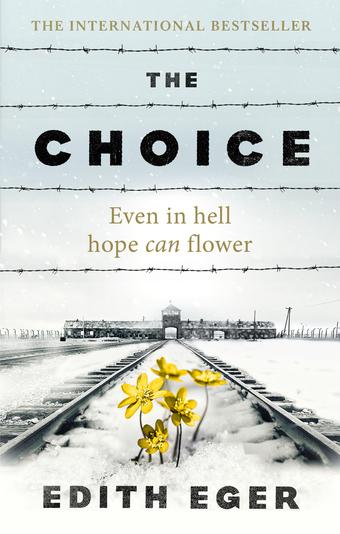

Book Review: The Choice by Edith Eger

The world marked the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau on 27th January 2020. In a remarkable and moving memoir Edith Eger recounts how she was sent to the infamous concentration camp in 1944 and survived to become an internationally acclaimed psychologist. Fergus from Donabate Library reviews her memoir, The Choice, which is one of the most-borrowed books on our shelves.

Eger published this debut work at the age of 90 and the first third deals with her ordeal during the war. It’s an incredibly powerful account of hope and perseverance amidst the inhumanity of the Holocaust. Edith spent her childhood in Kosice in modern Slovakia with her parents and her two older sisters, Magda and Klara. Her birthplace came under the rule of Hungary in November 1938 and this brought greater anti-Semitism and danger.

The presence of Hungarian Nazis (nyilas) grew stronger. The family were evicted from their first home and made to wear a yellow star. Her father spent eight months in a labour camp from August 1943 before returning home to what was a brief period of freedom. Edith was a talented ballerina and gymnast by the age of 16 but one day was told by her gymnastics teacher that she could not remain on the Olympic training team. Her sister Klara, an accomplished pianist, was away at a concert in Budapest in April 1944 when the family were rounded up with thousands of other Jews in the region.

They were all kept in grim conditions for a month on factory grounds at the edge of town. Edith searched the encampment for her grandparents and her first boyfriend, Eric, whom she had met at a book club. She found Eric and they made plans for after the war. Then the family were evacuated and put in a freight train. On the long journey her mother told her, “just remember, no one can take away from you what you’ve put in your mind.”

On arrival at the concentration camp, their father was first separated from the family with the other men. Then their mother was parted from Edith and Magda on the orders of the commanding Nazi officer. This man she came to know in the camp as Dr. Mengele.

She was told that day, by one of the prisoners acting as guards, that her mother was dead. That night she was forced to dance for the notorious Josef Mengele on the barracks floor as an orchestra played outside. Remembering her mother’s advice, she was able to dance imagining herself on the stage of the Budapest opera house. Mengele rewarded Edith with a small loaf of bread which she shared with her sister and fellow prisoners. This altruism later saved her life. The two sisters coped mentally with the brutality, labour, cold, lack of food, and terrible uncertainty of Auschwitz. Edith had one more encounter with Mengele. But their time in the actual camp wasn’t the end of the horror.

When Russian troops entered the camp in January 1945, a lot of the prisoners had been taken away on trains on a series of death marches. Edith and Magda were in one such group, having nearly been separated leaving Auschwitz. They were forced to march and work in different factories along the way. Perilously malnourished, they were even put on top of train cars carrying ammunition to deter Allied planes bombing them. Anyone in their group who got sick or collapsed on the road was killed. Their captors were callous, with one exception. The sisters and the remainder of their group crossed the Austrian border and ended up at a sub-camp in a forested area, Gunskirchen Lager, where inmates had been left to die. When American GIs arrived, they were buried beneath bodies but an unopened can of sardines that Magda had secured provided salvation.

Edith and Magda spent more than a month in the nearby town of Wels where their safety and security still felt unstable. They recovered enough to return by train to Kosice where they were miraculously reunited with Klara. She had hidden away in parts of Budapest and at one point in a nunnery. Edith’s relief at meeting Klara was tempered by tragic news about Eric and the dwindling hope that their father might have survived the war. She was diagnosed with several illnesses and had broken her back at some point in the last few months of the war. There were mistaken fears she had tuberculosis and on a visit to a sanitarium she met Béla, a man several years older, from an industrialist family who had fought in the partisan resistance. They married in November 1946 and had a daughter, Marianne, the following year.

Kosice was now part of postwar Czechoslovakia, where there was social and political upheaval. Béla became an adversary of the new Communist government as he wasn’t willing to cooperate with them. On New Year’s Eve in 1948 the family made a plan with friends to move to Israel within a year. In the worsening situation Edith had to find penicillin on the black market to help her ailing child. In May 1949, on a day as dramatic as any she had endured, she discovered that Béla had been arrested and was held in the nearby police station. Taking her child and passports, she devised a plan of action and by that night the three of them were in a train on route to Vienna, and from there to the United States rather than Israel.

During her early years in America, Edith did not talk about or acknowledge any of her experiences in the war, but the underlying trauma was there. She had a flashback on a bus in Baltimore when, speaking hardly any English, she misunderstood the payment system and drew the anger of passengers and the bus driver. A move from Chicago to El Paso turned out to be a liberating experience. By 1966 she had three children and decided to return to education. A fellow student recommended Man's Search for Meaning by Victor Frankl, an older Austrian psychiatrist who had been a prisoner in Auschwitz and Dachau camps. He had written his landmark book in 1946 and developed his own psychological concept of logotherapy.

Eger and Frankl corresponded for many years as she deepened her studies and tried undergoing therapy herself. In 1969 she received her degree in psychology at the University of Texas in El Paso. She then embarked on a doctoral internship at a nearby army medical centre. By 1978 she had a PhD in clinical psychology. Edith studied some of the major names in psychology and psychotherapy whose ideas she gravitated towards - Carl Rogers, Albert Ellis, and Martin Seligman. She still had flashbacks in daily life in instances like hearing sirens, seeing barbed wire or a policeman in uniform. She comes to see these moments as physiological manifestations of grief.

A pivotal moment in her life arrived when she was asked to address chaplains at a workshop in Berchtesgaden, Hitler’s former retreat in the mountains of Bavaria. With foreboding, Edith travelled there with Béla and they stayed in the same hotel room Joseph Goebbels used. She visited the remnants of the Berghof, or the Eagle’s Nest, Hitler’s former residence, and felt a sense of release. She then made the difficult decision to visit Auschwitz. She couldn’t persuade Magda, who was living in the States, to fly over as well. She and Béla reached Auschwitz just before relations between the Polish Communist authorities and the United States worsened and visits became impossible for almost a decade. There, standing alone in the women’s section at Birkenau, she remembered a fateful detail from the day she had arrived at the camp, something she had blocked from her memories.

Edith evolved her own version of therapy that she labelled Choice Therapy. “Time doesn’t heal. It’s what you do with the time.” There is a choice available to escape the past and find freedom and responsibility in embracing the possible. Eger sees forgiveness as a form of grief where we give up the need for a different past. These insights came alive in revisiting Auschwitz and her personal history. She has used her experiences and learning to help her patients. There are many examples of them in the book, from those contending with PTSD, anorexia, cancer, addiction, marital problems, racism, and depression. “How can I be useful to you?” is how she addresses those who come to her. Her life story is a testimony to a powerfully altruistic and resilient spirit that was nearly extinguished by the darkest forces three-quarters of a century ago.

Reserve a copy of The Choice here.

Edith Eger’s newest book The Gift is also available to reserve here.

Click here to reserve an eBook or eAudiobook copy on Borrowbox.

Call your local branch to avail of our ‘call and collect’ service:

Library branch phone numbers:

Balbriggan 8704401

Baldoyle 8906793

Blanchardstown 8905560

Donabate 8905609

Garristown 8355020

Howth 8905026

Malahide 8704430

Mobiles 8906719

Housebound 8604290

Rush 8708414

Skerries 8905671

Swords 8905582

We will continue to operate our delivery service to cocooners, the housebound, residential services and anyone with health issues. The cocooning library service can be contacted at 8906719/ 8604290 or email at [email protected]