Cú Chulainn and the Lady of Lusk

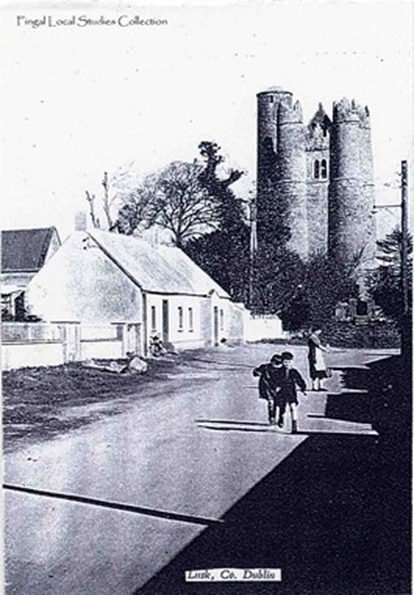

For the second instalment of Fingal Folktales, we are exploring a local tale from Lusk about how Cú Chulainn met his wife Emer. The story goes:

When Cú Chulainn the champion of Ulster heard of the beautiful maiden Emer he decided to visit her in her home in Lusk. He arrived there to find her sewing with her servant and asked her to return with him to Ulster to become his wife. She agreed immediately but left her servant to tell her father Finbolgwiley about the marriage. When Finbolgwiley returned to Lusk to discover the elopement he immediately set out with his soldiers in pursuit of the couple. He caught them at Balrothery and there challenged Cú Chulainn to battle. Cú Chulainn slew many of his men while his charioteer Lia drove them on towards Ulster. Finbolgwiley and his forces were eventually stopped at the river "Delvin" near Drogheda, due to a law forbidding anyone in pursuit or at war to cross the river. This allowed Cú Chulainn and Emer to get away safely. However, during the fighting Emer’s elder sister who accompanied Finbolgwiley was killed and later buried in a field at Balrothery called "Sennas Fort’’[1].

Several local versions of this story exist, and all are similar, but some versions specify that Emer recommends Cú Chulainn should court her elder sister instead of her[2]. A local Balrothery folktale also tells of the death of Emer’s sister but she is named as Scennend rather than Senna and is killed by Cú Chulainn at the Ford of Scennend[3].

Myth and Meaning

These local Lusk stories are all variants of a mythological tale called ‘The Wooing of Emer’ (or Tochmarc Eimhire in Irish) which is part of the Ulster Cycle. The longest and most detailed version of this story is found in a medieval manuscript called The Book of the Dun Cow (or Lebor na hUidre in Irish). In this version Emer’s father is named Forgall Monarch which can be translated as Forgoll the Wiley[4]. The name Finbolgwiley in the folktale version may be a distortion of this translation. Other differences occur such as the name of Emer’s sister being Fial rather than Senna and the name of Cú Chulainn’s charioteer is Loeg rather than Lia. In this version, Cú Chulainn must face many challenges before he can take Emer back to Ulster to become his bride. The challenges revolve around him travelling to Scotland to train with the warrior women Scathach, Uathach and Aífe.

The naming of physical features in the landscape is an element shared by both manuscript and folktale versions. In the manuscript version Cru Foit (blood turf), Glond-Áth (Ford of the deeds) and the Ford of Scenmnend are named from battles fought by Cúchulainn while bringing Emer back to Ulster[5]. The folktale versions also feature Senna’s or Scennend’s Ford named from the death of Emer’s sister. This type of place lore (called Dindsenchas in Irish) is a tradition which connects stories to landscape. While the place name Scennend’s Ford does not appear to have survived onto modern maps the Dindsenchas tradition is still alive today. The Fingal heritage office runs a fieldname recording programme called the ‘Fingal Fieldnames Project’ which records, researches, and preserves placenames in Fingal. You can explore the work of this project here.

Want to Delve Deeper?

If you want to explore further stories about Lusk, you can visit Dúchas.ie. Or if you would like to read the full manuscript version of the Wooing of Emer click here to access the Kuno Meyer translation hosted on Celt.ie. Or for a fascinating discussion of the Wooing of Emer, you can visit the Story Archaeology podcast here.

- Aoife Walshe

Bibliography

Archer, Patrick (1975), Fair Fingall, Dublin.

O’Curry, Eugene (1861), Lectures on The Manuscript Materials of Ancient Irish History, accessed through https://archive.org/details/lecturesonmanusc00ocuruoft on 20/03/2021, pp. 278 - 282.

O’ hOgain, Daithi, (1991), Myth, Legend & Romance: An Encyclopedia of The Irish Folk Tradition, England.

Rees, Alwyn; Rees, Brinley (1961), Celtic Heritage: Ancient tradition in Ireland and Wales, Great Britain.

The School’s Manuscript Collection, accessed through Dúchas.ie on 20/03/2021.

The Wooing of Emer by Cú Chulainn, trans. Meyer, Kuno, accessed through http://www.ucc.ie/celt on 23/03/2021.

[1] (SC, Vol. 0783: 61-63).

[2] (SC, Vol. 0786: 229; Vol. 0784: 140; Vol. 0783: 85; Vol. 0785: 60; Archer 1975: 13-17).

[3] (SC, Vol. 0784: 17).

[4] (O’Curry 1861: 278; O hOgain 1991: 134; Rees 1961: 259).

[5] (O’Curry 1861: 282).