25th Anniversary Series Blog 4

25th Anniversary Series Blog 4

Early 1900s – Public Libraries Flourish

The passage of a century provides a meaningful measure from which to take stock of bygone days and creates a pause in which to look expectantly to the future. At the turn of the 20th century in Ireland, the increasingly literate masses and the emergence of a newly reading public heralded a new era for knowledge dissemination. The Irish literary scene was thriving with prolific offerings, and many urban centres experienced a rejuvenated and bustling printing and publishing trade, whose wares reached far and wide, filtering through to the village library and reading room. Demand for literature was high, and there seemed a frenzied need to deliver.

Ireland’s ‘Top 100’

On 20 January 1900, The Irish Homestead journal published the top 100 reading recommendations for a village library, compiled by Irish writer, painter and critic, George Russell (A.E.), accompanied by an article on village libraries written by Father J. Donovan regarding the quality of available literature.

The list reflects topical Irish interests at the time – historical, cultural and otherwise – and was heavily influenced by the pervasive Irish literary revival. However, suggested reading material was not limited to subjects of home interest and included a varied compilation of international fiction, philosophy and history, such as Plutarch and the history of Mexico (1)(2).

Public Libraries (Ireland) Act, 1902

The proliferating and widespread demand for reading material, as well as the subsequent agitation for the extension of public libraries to rural areas, gave rise to legislative amendments that would be most beneficial to the movement to date. The Public Libraries (Ireland) Act, 1902 enabled the rural district councils to adopt the Act of 1855, while also allowing the councils to enter agreements with local schools to secure their use as libraries (1).

The United Irishman reported on 14 February 1903:

‘The Library movement is pushing ahead rapidly. All the County Dublin Rural District Councils have either adopted the Act, or will do so shortly’ (3).

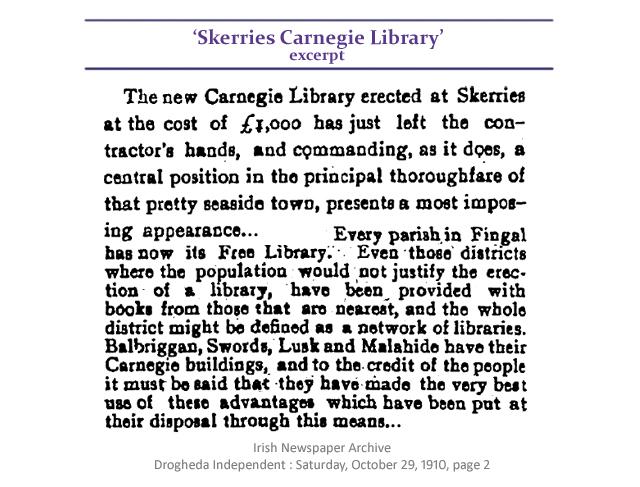

Legislation now granted country-wide provision for public libraries, and the Act was eagerly adopted throughout. However, the actual construction of physical, brick-and-mortar public libraries was slow to follow. The solemn fact was, under the Libraries Act, the monies raised from local taxation were scarcely enough to run a library service, let alone meet the financial outlay to build a library. Headway seemed unattainable under such circumstances, until word arose of the library-giving benevolence of Mr. Andrew Carnegie.

Mr. Andrew Carnegie

Mr. Carnegie was a Scottish-born American businessman and philanthropist who made his substantial fortune in the steel production industry in the USA. In 1848, at the age of 13, he immigrated to America with his parents. By this time, he had already gained a fond love of libraries. Never having lost sight of such opportunity of his youth, he wrote:

‘It was from my own early experience that I decided there was no use to which money could be applied so productive of good to boys and girls who have good within them and ability and ambition to develop it, as the founding of a public library in a community which is willing to support it as a municipal institution’ (4).

In 1881, Carnegie made his first gift of a public library, and rightly so to his native home of Dunfermline, Scotland. He soon sold his steel company and devoted himself to a philanthropic career; it would not be long before Ireland gained from his generosity. By early 1905, he had pledged almost $40,000,000 for 1,200 libraries in English-speaking countries, and of this money, almost $600,000 was for Ireland (4)(5).

Between 1897 and 1913, Carnegie promised over £170,000 to pay for the building of about eighty libraries in Ireland. Sixty-six of the libraries were built, and sixty are in use today. The flourishing of libraries throughout the country during this period resulted directly from Carnegie’s munificence, and by 1919, 81 per cent of the towns in Ireland which had rate-supported libraries received contributions from Carnegie (4)(5).

Carnegie did not formally promote his scheme, but accepted enquiries from interested local bodies that had discovered his generosity through newspapers and journals. Sceptical of unconditional acts of charity, believing it corrupted those in receipt, he was only willing to help those communities who were willing to help themselves. Stipulations in place for receiving a Carnegie grant were few but firm, and application layout was simple. In spite of this, submissions were oftentimes executed in an ambiguous and, shall we say, debatable manner by applicants. Such activity one would like to presume occurred unwittingly, but reports suggest to the contrary. To said applications, Carnegie’s private secretary was neither appreciative, nor amused (5).

James Bertram became Carnegie’s private secretary in 1897 – the year that saw Ireland’s first request for a Carnegie grant. Bertram’s role was to handle Carnegie’s vast wealth, and being fully committed to the position, he did so in a purposeful and methodical fashion – as well as with a rather individualistic, candid approach. Regarding the submission of a large-scale plan by Blackrock Urban District Council which resembled that of a dancehall with little provision assigned for a library service, Bertram rejected the application, stating ‘…as less than [certain floor area]… [is] devoted to the Library…’. In response to a revised plan, he replied, ‘Mr. Carnegie is not building a Games Room’ (4).

A Library by any other Name

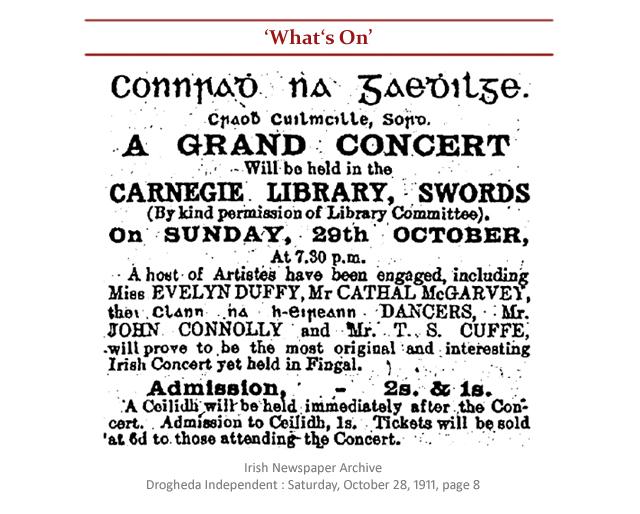

Tempted by the free offerings of large sums of money, many local bodies secured grants allowing for the construction of buildings far in excess of the requirement of a library service. This posed a ‘problem’ – what to do with all the undesignated space. The solution? Dance, of course!

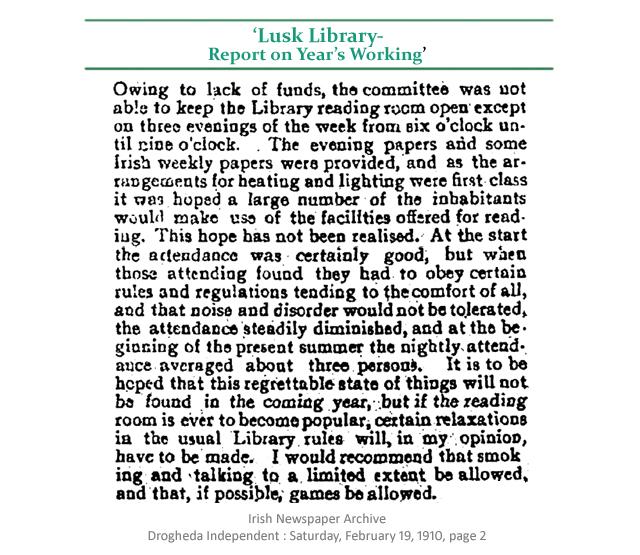

Local records provide an insight into social activities of the time. Crossroads be gone, entertainment now took place in the local ‘hall’ – library by day, social club by night. The library embedded itself as the central hub of the community, and it was not a rare occurrence for one to enter a library, only to be greeted by a smirched, smoke-filled setting courtesy of a generous gathering of card-playing and gambling enthusiasts. However, it was the dance fever of the 1920s which firmly found footing, so to speak, in these buildings. True to the prevalent Irish cultural revival of the era, dancing was to be strictly of the Gaelic variety. In the early 1920s, Swords Library Committee agreed that ‘promiscuous Dancing [jazz] in the Swords Library is prohibited, but Irish Dancing can be carried out as usual’ (4).

Unquestionably, such activities enhanced the lives of those residing in rural districts, though such use was never the intention of Carnegie, whose aim was to better the citizenry’s day-to-day drudgery through education and knowledge. Behaviour in city libraries was conducted in a more congenial fashion, and dutiful to Carnegie’s intentions, they became the pillars for further development of the public library system.

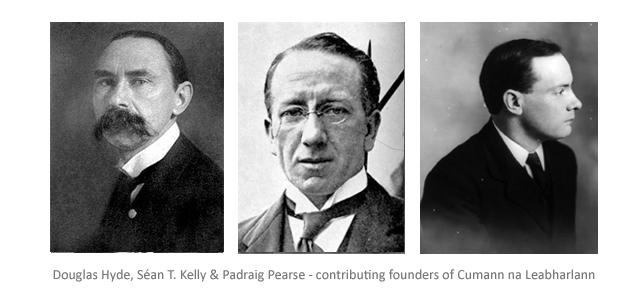

Cumann na Leabharlann

The notion of res republica was never too distant a will of those who championed the public library movement in Ireland. In a continued endeavour to further the now-existing propensity for reading, and the consequential related improved prospects for the people, in 1904 Cumann na Leabharlann (The Library Association) was established. Among the founding members of Cumann na Leabharlann were Douglas Hyde and Sean T. O’ Kelly (both who would subsequently serve as presidents of Ireland) and Padraig Pearse, a leader of the 1916 uprising. The dictum of the association was that it be ‘of Ireland and for Ireland’ (1)(2).

An ambition of the association was to situate Ireland in a capable position whereby opportunities existed to better oneself (namely through study and reading) and to create a nation of thinkers better able to serve their country. Disheartened by the lack of quality material available to the country’s youth, it was bemoaned that cultural and intellectual experience halted as soon as formal schooling ended. Regrettably, there existed little in the way of healthy attractions to entice these youths – often their only outlet being the public house or the street, neither of which led to much in the way of beneficial accomplishment (1).

Cumann na Leabarlann worked to mobilise local authorities to provide widespread opportunities for reading and study by establishing newsrooms and libraries throughout the county. Library staff were encouraged to take notice of their honoured position which afforded them the chance to exert positive influence by enticing non-readers to the library, thereby contributing to the creation of a learned – and thus formidable – nation (1).

Newspaper Rooms

A staple of most libraries of the time was the newspaper room. It was a valiant idea, the aim of which was to entice non-readers to libraries. Dr. Lyster of the National Library described newspaper rooms as ‘a civilising influence for the tired labourer or artisan’, and another comment of the time suggested their use as a method ‘to introduce and maintain order and quietness and help prevent drinking and gambling’. (2) The outcome proved successful if one is to evaluate such in terms of custom – this use seems to have superseded any other library service. Committees facilitated this demand due to the low initial outlay for stock, though the endeavour rapidly proved itself an undeniable affliction in many a librarian’s life. Writing on the subject of public library use in 1907, Amian Champneys remarked:

‘The atmosphere of public libraries in general, and of newspaper rooms in particular, has become a proverb, and will in all probability continue in this evil notoriety so long as the news-room continues to afford a free and agreeable shelter to the unwashed.’ (4)

The reputation earned was owing to the apparent ‘lower tone’ set by the newspaper room clientele – a smoking, sporty crowd from whom profanities were often known to abound. Such supposed impropriety forced several library committees to provide a separate room for ladies, believing them to be of a more becoming nature and possess proper sensibilities.

However, opinion later shifted, proclaiming the need for a shared room. It was asserted the presence of ladies would serve to raise the tone of the newsroom, lending a certain merry and sanguine feel. And besides, while disparate, the ladies’ room fell foul to tall tales (4).

In an early edition of Free public libraries, Thomas Greenwood wrote:

‘A separate ladies’ room means often a good deal of gossip, and sometimes it is from these rooms that fashion sheets and plates from the monthlies are most missed. Ladies need not faint at this statement; but it happens to be unfortunately true’ (4).

Libraries for the People – Literature for Minds and Morals

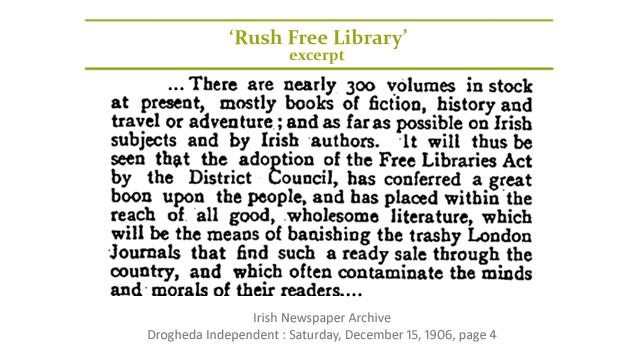

The ambition of a sweeping nationwide library service which extended to all quarters of the country – rural as well as urban – became a key focus of many. Organisations and individuals often advocated for small circulating libraries to help deliver services to areas of a more remote locale, and so distribute reading material to all (1).

In those early days, the calibre of reading material that proved most popular to library frequenters – particularly those of the newspaper rooms – did not always fall within the high, or even appropriate, standards of certain champions of the movement. Such campaigners’ intentions were, firstly, to provide reading matter of substance to the people, and secondly, for that reading matter to be of a noble and moralistic value, which was thought more suitable for an Irish audience.

Father J. Donovan was one such proponent. He commented that many library users ‘for the most part read nothing but wretched trash’, usually ‘low London productions which are neither good literature nor good morals, papers that often pander to the lowest impulses of man’s depraved nature’. Such productions included ‘Ally Sloper, Comic Cuts, Chips, The Budget and other similar London abominations’ (1). Potent words from a man unequivocal in his beliefs and intentions – a genuine conviction to help and protect the people, and in doing so, allow them to help and protect themselves – that no doubt helped set the scene for the later Censorship Board.

The first quarter of the 1890s experienced an unrivalled growth in rise of public libraries in Ireland, that of which had not been seen before, or, in fact, since. Public libraries appeared scattered across the country, the uneven distribution a direct consequence of the application process to obtain the invaluable Carnegie grants. Where libraries were not established as physical structures, circulating services were arranged. The movement strove to bring knowledge and education to all, to meet the surging demand for literature, to espouse all that was Irish, and to create a nation of thinkers of which to be proud.

By Laura Flanagan, Fingal Libraries

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

Next Monday, July 29th: Librarians of the 1900s, Carnegie United Kingdom Trust, Censorship Board, and much more!

We hope you join us!

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

For your interest:

Fingal Libraries Local Studies and Archives is a repository of photographs and documents, private and donated collections, encapsulating visual and literary snapshots of Fingal and the Dublin area through history.

It is a treasure trove for anyone looking to unearth the rich culture and heritage that is the region of Fingal. Staff are exceptionally knowledgeable and always willing to help in your research.

Thanks to Catherine, Brian and Karen for allowing access to archives for this blog series.

Research material used in the blog series can be found through the Encore catalogue on Libraries Ireland website:

University of the People: celebrating Ireland’s public libraries: the Thomas Davis lectures 2002. An Chomhairle Leabharlanna. 2003 Call No. 027.4415

Public libraries in the 21st century : defining services and debating the future / Anne Goulding. 2006. Call No. 027.44

A history of literacy and libraries in Ireland : the long traced pedigree / Mary Casteleyn. 1984. Call No. 027.0415 Ireland

Irish Carnegie Libraries : A Catalogue and Architectural History / 1998. Call No. 027.4415

Dublin Libraries : A Pictorial Record / Lennon, Sean. 2001. Call No. 027.0418

Another invaluable resource during research included the Irish Newspaper Archive, available for use on public PCs at your local Fingal Library.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________

(1) A history of literacy and libraries in Ireland: the long traced pedigree / Mary Casteleyn. 1984.

(2) Kiberd D, The Library and Imaginative Freedom. In : McDermott N. (ed) The University of the People: celebrating Ireland’s public libraries: the Thomas Davis lectures 2002. Dublin: An Chomhairle Leabharlanna; 2003. p.79-89.

(3) Hardiman N, Haunt of the Idlers or Centre for Learning? Public Libraries 1849-1949. In : McDermott N. (ed) The University of the People: celebrating Ireland’s public libraries: the Thomas Davis lectures 2002. Dublin: An Chomhairle Leabharlanna; 2003. p.13-29.

(4) Grimes B, Carnegie Libraries in Ireland. In : McDermott N. (ed) The University of the People: celebrating Ireland’s public libraries: the Thomas Davis lectures 2002. Dublin: An Chomhairle Leabharlanna; 2003. p.31-41.

(5) Irish Carnegie Libraries : A Catalogue and Architectural History / Grimes, Brendan. 1998